Lessons from centuries old human rights violations in Canada

Though I truly have become a global citizen – I am and always will be proudly Canadian. Well, proudly until the middle of this year… In May, 2021, members of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation discovered the unmarked graves of 215 children on the grounds of a former residential school, that was in operation between 1890 and 1978 in Kamloops, B.C. The residential school system is a painful part of Canadian history, where indigenous children were stripped from their homes and cultures and forced into these institutions, where they were subject to cultural ‘cleansing’ and abuse. The school in Kamloops was one of more than one hundred such places, and the final residential school only just closed its doors in 1996.

Orange Shirt Day is a day commemorating the thousands of students lost in the residential school system along with the survivors. It started in 2013, where the story signifies a residential school survivor remembering being stripped of her orange shirt, in the first of many violations she faced when forced into the system. This year, the government of Canada has announced a new federal holiday, National Truth and Reconciliation Day, to honour the victims and survivors of the residential school system.

So, what does all of this have to do with forest investments in the tropics?

These long and hard learned lessons from Canadian history continue to be fought around the world, coming back to an underlying current; violation of indigenous rights. In forest investments in the tropics, this manifests in tenure disputes, forsaken land-use rights, and multiple forms of disrespect for local people.

So, in honour of Canada’s first National day of Truth and Reconciliation last week on September 30th, I wanted to write today about various approaches to ensure that indigenous rights are respected in executing a responsible forest investment strategy in the tropics.

An integrated approach to upholding indigenous rights

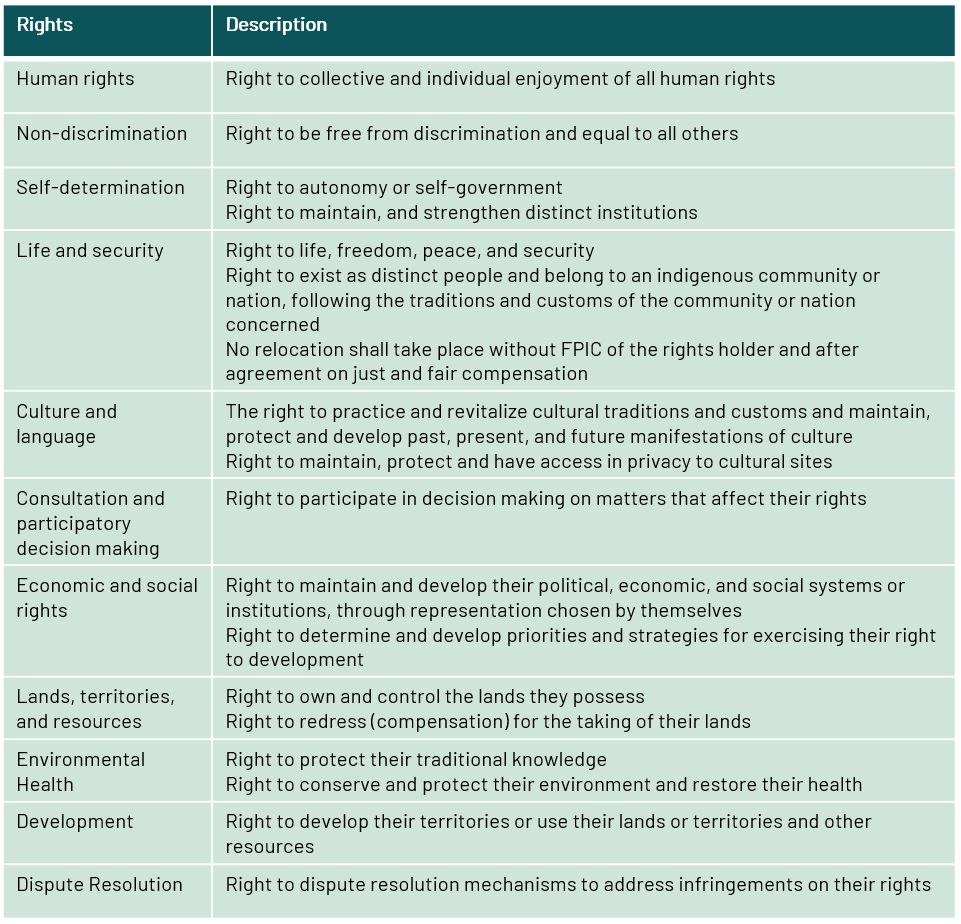

There is a good chance that if you have a forest investment strategy targeting tropical geographies that one of your most important stakeholder groups will be indigenous or otherwise marginalized local neighbours. Respecting the rights of these stakeholders is your responsibility and is absolutely paramount for a long-term sustainable business. Upholding indigenous rights begins long before your investment becomes operational and extends until you ultimately exit the investment. In fact, you should set a precedent, so that maintaining positive indigenous relations for your successor investor becomes status quo (shouldn’t it be already?). To give an indication of what I refer to when I speak of the broad spectrum of indigenous rights, I have extracted the following table from FSC’s Free, Prior and Informed Consent Guidelines, where human rights identified by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the International Labor Organization that are associated with forest management are listed.

To be sure that rights are not only identified and respected, but strengthened with your forest investment’s activities, I provide some guidance here on different approaches that can be taken to ensure that upholding indigenous rights is built into your management process.

Stakeholder identification

Early in the investment process, both in strategy design, and in carrying out due diligence on specific investment opportunities, stakeholder identification will be one of the first steps you take in your evolving relationship with indigenous people. You will identify indigenous people either within or near your management area, you will gain an understanding of their customary and legal rights and how these might be affected by your management activities. You will discover threats to ensuring the protection of their rights and likewise identify possible mitigation measures. However, before acting on anything, you will carry out the next step of Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Free, Prior and Informed Consent

In the context of responsible forest investment management, Free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) is part of what should be included in a well-documented and executed stakeholder engagement process.

Upholding FPIC with indigenous people or local communities, when they are identified as an affected legal and/or customary rights holder, is a requirement of FSC as related to their being affected by management activities. FSC provides managers guidance on how to address FPIC through its guidelines. There is no short definition of what FPIC entails, but the main components can be summarized as follows:

FREE – Where rights holders voluntarily and unencumbered by coercion, are made aware of their ability to grant, withhold, or withdraw their consent to proposed management activities that affect their legal and/or customary rights. This process shall respect self-directed and/or traditional decision-making processes of the rights holders.

PRIOR – Decision is sought from rights holders far enough in advance of any authorization or commencement of management activities, at the early stages of management planning. Time is provided for the rights holder to understand, access, and analyse information on proposed management activities before any decisions are taken.

INFORMED – The type and format of information provided to rights holders is accessible to all. It is complete in its description of the proposed management activity and associated potential impacts, and it informs the rights holder of their voluntary ability to grant, withhold or withdraw their consent of the activity.

CONSENT – The decision to exercise the right to grant, withhold, or withdraw consent to proposed management activities that affect legal and/or customary rights. It is not a one-time decision, but part of an iterative and ongoing management process. Consent is not the same as engagement or consultation. It is the expression of rights.

FSC guides practitioners through a 7-step FPIC process as follows:

Step 1: Identify rights holder and their rights

Step 2: Prepare for further engagement and agree on scope

Step 3: Participatory mapping and assessments

Step 4: Inform affected rights holders

Step 5: Affected rights holders deliberate and decide

Step 6: Verify and formalize FPIC Agreement

Step 7: Implement and Monitor FPIC Agreement

Basically, FPIC includes very early engagement with indigenous people, prior to management activities taking place – where they are informed on how their customary or legal rights may be affected by management activities. Upon consent, an agreement is made between the parties regarding their ongoing engagement. FPIC continues as the project develops and evolves.

Ongoing stakeholder engagement

As I alluded to, FPIC is not something you do once and then you tick off the box that it is complete. As your forest project evolves through different phases of development, or the context changes in some way, FPIC is revisited. Likewise, there is an ongoing commitment to engagement. This builds both the relationship and trust, it builds respect and creates an open-door policy of sorts between the forest company and the indigenous people impacted by your forest investment. It is important in this ongoing engagement that there is a trusted person, or team that can regularly be the face of the forest company, to share opportunities and overcome challenges.

Dispute Resolution

Every person is different, with different needs and expectations, and though in your forest investment, your stakeholder engagement will aim to respect the rights of the majority, there will be instances where indigenous rights are either not respected or not perceived to be. It is in these (hopefully few) cases, there needs to be a transparent and robust dispute resolution mechanism in place. Where indigenous people can safely raise grievances and have them addressed. Though the process may adapt over time, the importance of consistency in how it is applied is extremely important to maintain trust. Another important distinguishing feature of dispute resolution is for both parties to be aware of the limitations of your business in the dispute resolution process. Depending on the context of a dispute, it may be necessary to engage law enforcement, local governments, or some other institution, better equipped both in terms of the law and in terms of expertise to address the dispute.

Needs alignment

One of the most responsible ways you can engage with indigenous people as a forest investor in the tropics is to take an approach based on needs-based alignment. This is responsible to shareholders; in that you look for opportunities to both reduce investment risk and secure or increase value by your engagement. It is responsible to the indigenous communities themselves in that you address their rights and their needs and look to reduce the risk of negative impacts on their rights, while also looking for ways to provide them with increased opportunities – to allow for a better situation for the indigenous people than how it would have been in your absence.

This could look like setting aside culturally important areas to the indigenous people from commercial forest management or providing them with well-paying jobs. It could be having a stakeholder board, where the indigenous community is present and has a voice in ensuring indigenous rights are being upheld.

Parallels between the orange shirt and forest investment

The indigenous people of Canada and their cultures have been repressed for centuries. Speaking generally, the European settlers to Canada were not just disrespectful, they were harmful. They came with an attitude that their way was the best way, the only way. Basic human rights were violated, and as such, centuries of loss, suffering and conflict have resulted. Though I am shamed by this part of my country’s past, I am hopeful that those hard lessons learned will pave the way for a more equitable future.

In the same vein, foreign forest investors in the tropics could be seen as the European settlers arriving in Canada for the first time – thinking that their resources, forest management expertise and knowledge of capital markets and western standards of development are the way forward. Unfortunately, where this attitude has prevailed is where land-grabbing thrives, green-washing often originates, biodiversity declines and human rights are violated.

Collaboration is the way forward, and if you would like to talk about your forest investment strategy in the tropics to understand if you are adequately addressing Indigenous Rights, please reach out.