On the back of the release of IPCC’s latest climate report a couple of weeks ago, the outcry for action has never been louder. Nor has the opportunity ever been greater to reverse the trend with the power of nature. Conservation efforts at preventing deforestation and forest degradation prevent further emissions from taking place, but restoring nature can absorb emissions and reverse the trajectory. Forest restoration is not only a climate solution, but if done well, can deliver numerous commercial and sustainable development benefits.

Ecosystem marketplace in their latest State of Forest Carbon Finance (June, 2021) has summarized that forest carbon interventions (for example through afforestation/reforestation, restoration, and conservation), particularly in tropical forests, are among the most significant and cost-effective solutions for climate action, capable of providing up to 1/3 of climate mitigation needed by 2030. Yet this area receives less than 3% of climate mitigation funding. Though I don’t have any hard numbers to back my hypothesis, I suspect that more money (or at least a substantial amount) is being channeled into discussing the same problems again and again trying to come up with new ways to get few, unique restoration projects off the ground, than is actually going into the ground.

To get out of the niche and into scale and replication, I believe there needs to be less talk, and more meaningful collaboration between seed funders and commercial investors. In this article, I provide a bit of background on the urgency of tropical forest landscape restoration and identify some structural challenges in the investor universe for the forest investment lifecycle, and how these can be overcome, highlighting some good examples.

NASA proves the problem, private capital can provide the solution

As mentioned, to realize the climate benefits of forests in tropical settings, forest landscape restoration efforts need to occur at scale, and to do this, private capital is required. Private capital, the largest source of funding available – massively trumps public, philanthropic, and multi-lateral sources (the World Economic Forum estimates annual donor funding to be in and around USD 250 Billion, or less than one percent of the USD 400 Trillion available by banks, institutional investors and asset managers).

The main challenge of course is that when it comes to forest investment, private funds tend to flow to developed geographies, where lower risks are perceived than in developing geographies. Sustainable forest investment in these core, developed markets is a good thing, but it is not enough to address the climate challenges we are facing. There is little climate additionality. What I mean here, is that in most cases these forests are already managed with high sustainability standards, creating long-term climate benefits in a renewable cycle, but additional investment does not generate the same magnitude of additional climate benefit.

In the tropics however, the story is different. Funding is not flowing to forest projects in the tropics despite both the investment and impact potential. On the investment side, rapid biological growth rates are complemented by an increasing wood demand that exceeds supply. On the impact side, in addition to the numerous climate benefits, there are opportunities to enhance biodiversity, improve soil and water integrity, and create socioeconomic benefits such as rural job provision.

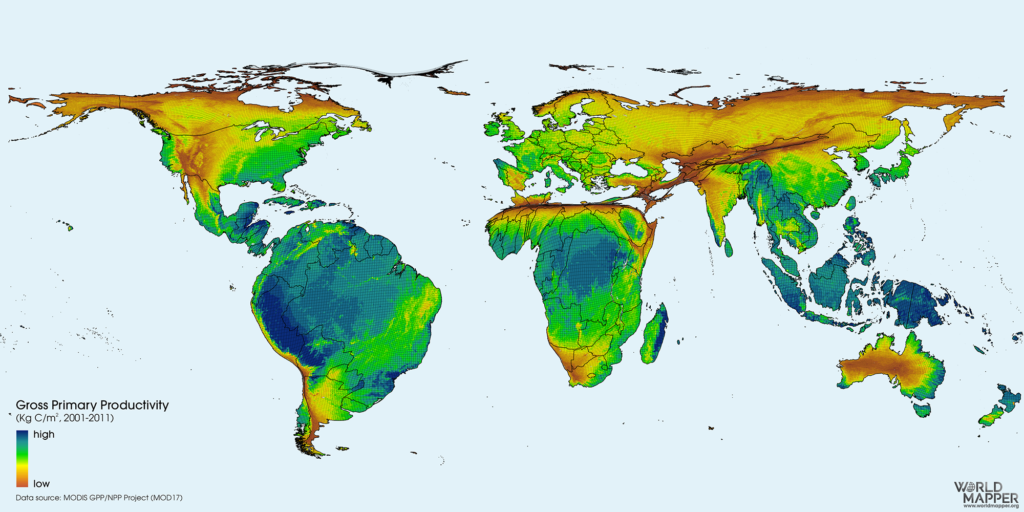

When considering climate, Nasa has recently published an article, where it finds that tropical forests’ ability to absorb carbon dioxide is waning. This is extremely alarming. Take this figure below from 2018, where Nasa satellite observations were used to create an annual Gross Primary Production (GPP) of the biosphere on land, measured in gC/m2, that plants create by capturing sunlight and CO₂ during photosynthesis. Though there is an animated version that shows the change in productivity regionally through the seasons, this static image shows the annual average productivity picture, illustrating that natural ecosystems are most productive in the tropics (exclusive of desert areas).

In NASA’s recent analysis that covers the period between 2000 and 2019, they have studied how forests have behaved as sources or sinks of CO2. Over this period they have found, the total amount of carbon emitted and absorbed in the tropics was four times larger than in temperate and boreal regions, but that tropical forests absorption potential is declining due to large scale deforestation, degradation and climate change. The study showed that 90% of the carbon absorbed by forests globally is offset by deforestation and forest degradation processes. We need to halt deforestation and reverse degradation to rectify this. This of course costs money, and to attract the big bucks, it needs to be packaged up into a compelling and realistic commercial investment opportunity.

The tropical forest conundrum

Let’s break down this tropical forest paradox into its simplest form:

The biological context

- Tropical forest areas are the most productive

- Tropical forest areas are a larger source of emissions than temperate and boreal areas

The investment context

- Temperate and boreal areas (developed markets) receive the majority of investment funds

- Risks are lower in temperate and boreal areas

- Tropical geographies have immense investment potential with favourable biological growing conditions and unmet wood demand

From the standpoint of forest landscape interventions to reduce global warming, tropical forest areas are both the greatest opportunity (ability to store more carbon, faster) and the greatest threat (large existing carbon sinks at high risk of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) yet receive the least amount of funding. Sustainably managed, lower productivity temperate and boreal forests are receiving the lion’s share of private investment capital.

The reason for this is simple – risk

Until risk is addressed meaningfully – private, commercial capital will continue to stay clear of forest investments in the topics. The purpose of this article is not to get into the details of risk, but I would be failing to paint the picture of why private capital is difficult to come by if I didn’t at least touch on them. So, the synopsis of these is:

Long time horizon: several years until an early-stage forest project is generating cash flow,

Political risk: government and regulatory stability, corruption/bribery, weak law enforcement,

Tenure risk: tenure security, customary and informal tenure, tenure conflict,

Market risk: immature market development, informal or illegal markets,

Financial risk: secure financial infrastructure, volatile currencies and unfavourable tax regimes,

Management: lack of track record, management, silviculture and business expertise,

Climate and biological risk: drought, fire, flood, storm, pests, disease, species and genetics selection, biodiversity decline,

Social risk: legacy or potential stakeholder conflict, and

Exit risk: lack of potential successor investors.

I’m not trying to sugar coat it; these risks exist. Of course, not all of them in every context – BUT THEY CAN BE MITIGATED!

More collaboration is required across the forest investment lifecycle

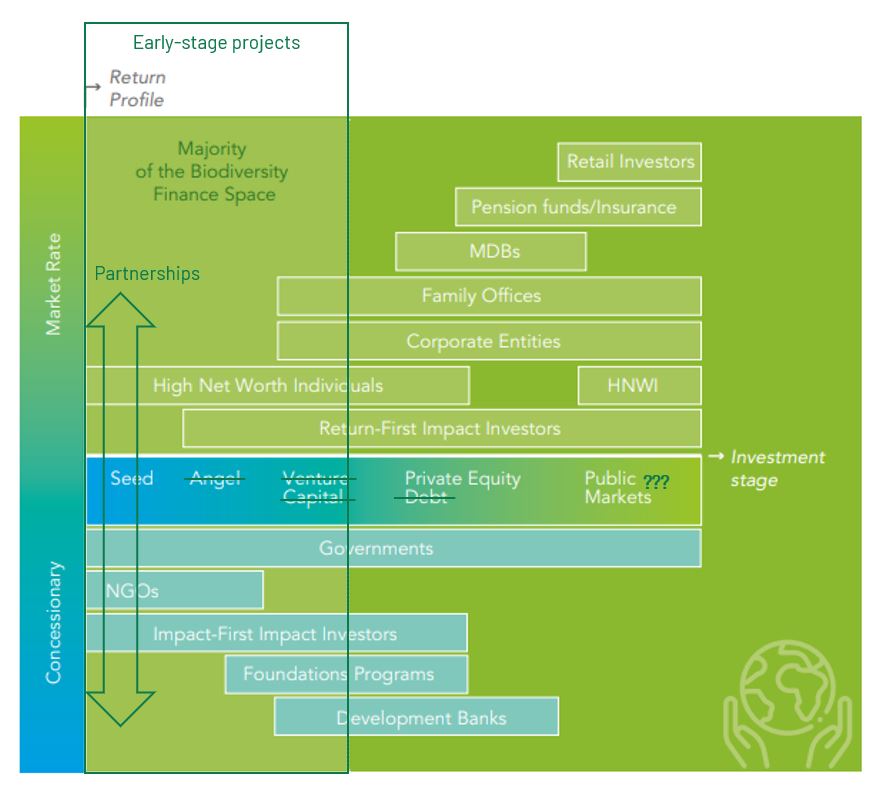

How private capital tends to address these risks is by avoiding greenfield, or early-stage projects all together and coming in at a later stage, when the project has already been de-risked. This, however, gets us nowhere on restoring degraded forests. The following figure is borrowed from the World Bank report on Mobilizing Private Finance for Nature (2020). Here the World Bank has illustrated the investment universe for biodiversity projects. Though for the most part, I believe the illustration is well-suited to forest investments, I think some elements warrant adjustment.

In this figure, I notice that most of the investment sources indicated by the World Bank apply to the forest investment sector in the tropics. However, there are some clear non-conformities (my adjustments to the figure are illustrated in dark green). Angel and Venture Capital normally are not sufficiently patient to withstand the long-time horizons of forest investments. Debt does show up on the figure at a later stage, but I would only argue that debt is only a viable short-term solution if the forest company is generating revenue. I am also yet to see a forest investment in the tropics go public (apart from some large-scale plantations associated with the pulp and paper sector). One glaring challenge I see with this illustration, which is a very real problem is the siloed sources of funding throughout the various investment stages. Often the seed capital provided by donors, impact-first investors, or other catalytic capital providers finance an early-stage project, completely disconnected from the objectives or investment requirements of later-stage commercial investors. Donor funding will be heavily focused on achieving impact objectives, such as natural forest restoration, conservation, and improved land-use practices, without due attention to financing activities that will enable private capital to invest once the project has grown-up. For this to work, I believe early partnerships are required, AT SCALE, where commercial investors commit to make an investment, if early-stage seed capital successfully reaches de-risking milestones.

Some good examples

The TA facility within the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund is a good example of where this model is taking place. There is a clear link between the TA facility capital’s objectives with that of the commercial investor.

Another initiative to follow is the Demeter Initiative, which is creating a blended finance vehicle that will enable private investors to enter into the natural capital space more easily, with a larger reach and more efficiency than a number of the other public or philanthropic seed capital vehicles.

Despite the ability for forest landscape restoration interventions in the tropics to reverse climate change, we don’t have time to change the fundamental approach of large private institutions when it comes to considering these early-stage opportunities. We don’t have time to spend resources drumming up “innovative” and complex financial structuring mechanisms that are only suited to isolated cases.

We need simple and replicable collaboration among different sources of funding with different risk-return-impact appetites, where all parties are brought to the table at the outset, joint objectives are agreed, and an investment program is put in place to achieve them.

Call to action

I need your help. I’m on a mission to attract new impact investment to forest investments in the tropics. This autumn I will be providing resources to support investors new to the space to make well informed investment decisions in these geographies. If you are new to the sector, I would love to hear what would help you on this journey. Please take a short survey here to provide your input. If you are a seasoned practitioner, I would also like to hear your thoughts on what new investors need to enter the space. Please provide your thoughts here.

I’ve created this Theory of Change guide to get your impact investment strategy off to a running start. To stay up-to-date on additional resources I release, you can sign up to my newsletter here – or just send me an email and we can set up a call.